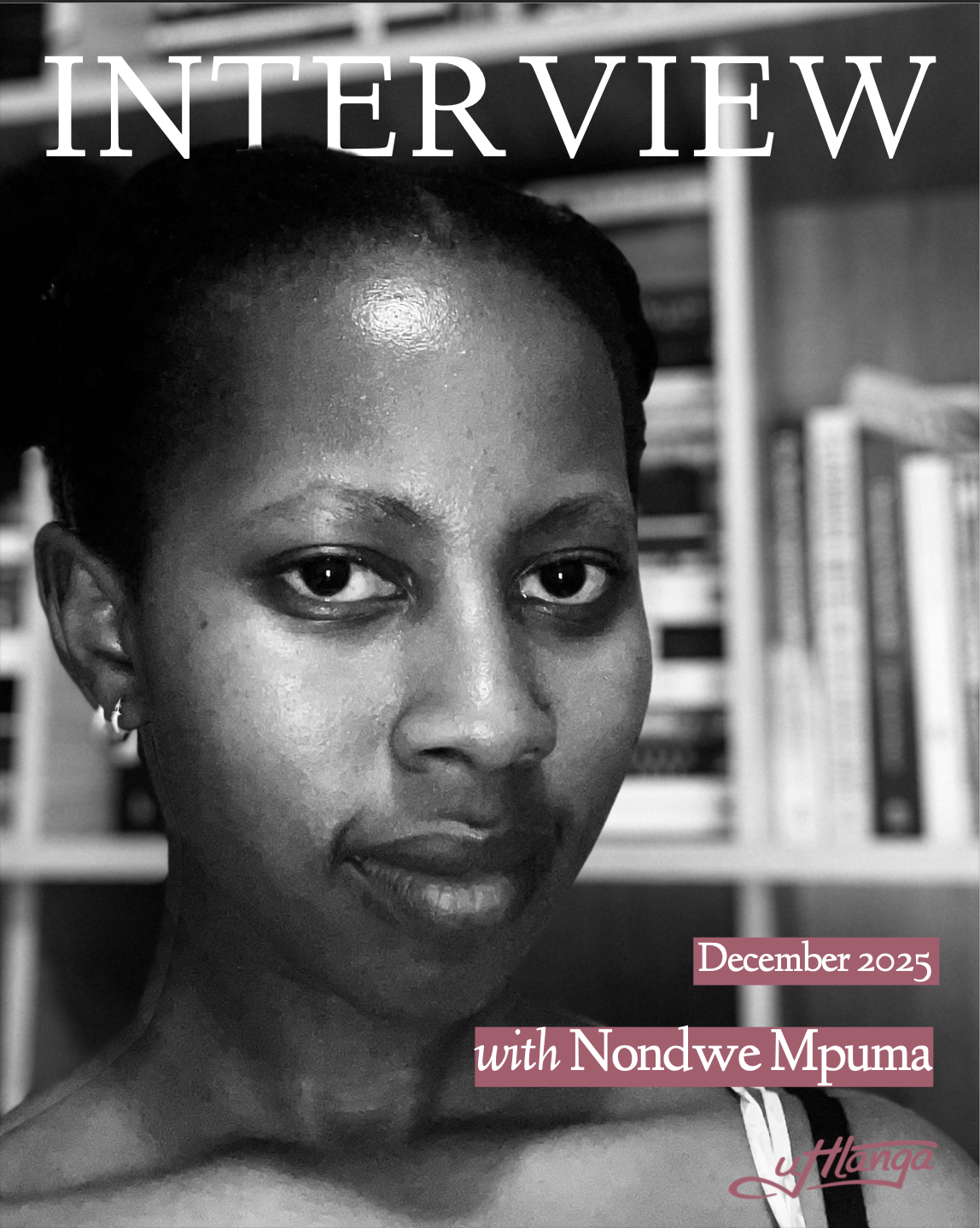

NM: Oh mkhaya! Hahaha. I think we must first establish that ndingunolali, a farm-Julia, at heart.

There is something about the Eastern Cape in December, a little bit of magic. Our return with all the evidence of our “gold digging” elsewhere. It’s the people, familiar faces who know to greet strangers. It’s summer fruit ripening, the ploughing season, hot sun and thunderstorms, the smell of the soil when rain teases, the sun dancing on Christmas morning and the food (meat), the endless family visits and celebrations. I think it’s coming back to this, or the memory of this, that beckons me home.

MR: In the poem, ‘There is a goat for every occasion’, you end with this line:

“It’s no wonder I glow”

Each time I read this line, I’m left with this deep sense of a chuffed little girl, or not-so-little girl, who is quite literally and also figuratively glowing with the pride of her community, and the supernatural, and a sense of utmost belonging.

Is this “I” you? How autobiographical are these poems? Are there poems where you have moved through different characters, or peoples’ perspectives?

NM: It is funny that you chose to ask me about “There is a goat for every occasion”; the last line is tongue-in-cheek. The “I” at the end is me, but the poem itself contains an amalgamation of experiences which are not all mine.

There are poems which are partially autobiographical, but I think I always write from an imagined “I” which allows me to embellish. I think in most of the poems I am moving between myself, my imagined self, other characters and other people’s perspectives.

The only poem that is purely autobiographical is “Childhood”; in the same breath, this nostalgic experience of childhood is one I share with so many others who have grown up in rural South Africa that the poem becomes one that is from a shared perspective rather than my own.

MR: In ‘IBhayibhile yesiXhosa’, you write:

“uQamata has always been a god of loss –

lost teachings

and prayers

and subjects.”

In your estimation, what can poetry do to or for loss? Can it be more than a witness; can it actually become something that bridges that loss?

NM: Poetry unearths what is buried, sometimes what is hidden and ignored. Poetry allows us to pick on festering wounds. Loss tends to be something that gets buried or ignored or hidden. So, yes, poetry can be more than a witness: it can be a mirror which reflects what loss has done to us or to show us who we’ve become because of our loss, which then presents opportunities to decide to confront our loss. Poetry can also be a pathway to grieve loss, and this pathway becomes a place from which we begin to heal what can be healed, restore what can be restored and accept what cannot be restored.

MR: Still thinking about poetry’s potential roles or capabilities beyond the page – do your poems function as a form of veneration? In this case, perhaps directing that veneration towards the all-encompassing God of AmaXhosa, uQamata, as opposed to the ‘Christianised’ deity, uThixo?

NM: Yes, in this poem particularly there is a respect for uQamata as opposed to uThixo, whom I hold great respect for too. The question I was trying to ask and answer in this poem is what happens when there is a god without scripture. uThixo is essentially prescribed while uQamata is a God without The Word – what happens to such a god? I’m attempting to make sense of the choices made by person like Tiyo Soga when he was revising the isiXhosa bible; what if he had said God was Qamata? I imagine that would have converted Xhosa people far quicker than the creation of a new god. Would people have carried over teachings and prayers into Christianity? What would have become of people’s earlier interpretations of the bible? These are things that I think about every now and again considering that I grew up around amaqaba and have always admired their ways of doing. I’ll stop now; this is a very long answer to a very short poem that I sometimes forget I wrote.

MR: In this world where “rain is a memory”, where roads are “snarky” and prayers are “mumbled”, you’ve so beautifully captured a deep sense of restlessness: of spirits, of people. And perhaps of the land itself, this land of tornadoes, and an ocean that you resist, knowing the potential for you to become its “prey”. That’s me fan-girling. But now, here is me asking: was writing this collection a means of confrontation, too? And of centering the specificities of what Niyi Akingbe calls the “marginality” of the people you write about?

NM: I wrote some of these poems as means of confrontation and I really wanted to center the rural space and its people in ways that go beyond the adverts of “poor Africans” sent abroad, the description of a degrading people in Cry, the Beloved Country and the general snarky perception of rurality in urban spaces.

MR: Building on my previous question: was writing this book also an opportunity for you to confront the many god(s) of the Eastern Cape, and their colonial and precolonial histories and narratives? I’m thinking here of the name ‘Mount Ayliff’ itself, and eMaxesibeni’s positioning in the missionary narratives of the Roman Catholic church, and the Comboni religious order?

NM: I never really thought about confronting gods as such. I thought about reflecting the kind of magic that I see in a place like Lubaleko. I wanted to capture that though a dreamlike, blue etherealness. I wanted the confrontation to land gently, to not be an attack or otherwise belittling. The gods come from far beyond the Eastern Cape.

It is only as an adult that I have begun to understand Lubaleko from the perspective of Mount Ayliff. I have always understood emaXesibeni (Mount Ayliff) from the perspective of Lubaleko. To explain this a little bit more, I spent the majority of my childhood never going to town. I’d always understood Lubaleko to be the center of the universe because the king of amaXesibe comes from there, and my grandfather, having come from a line of advisors, insisted on passing on this kind of knowledge.

My grandfather had always taught us about the development of Lubaleko where one of the oldest churches is a Roman Catholic church, which was an outpost for the Mount Ayliff mission. I understand that the Comboni religious order was something that came about in the 1990s in Mount Ayliff and has since lapsed, but cannot engage with this further as I spent some of my childhood going to the Anglican church and the majority of my tine as a parishioner at the Presbyterian church. I have a very colourful experience with religion(s )beyond emaXesibeni, as I spent a significant portion of my childhood in Durban and that crept up in some of the poems.

MR: You do so much in this volume of poetry. It is slim and yet that’s where its connection to smallness ends; this is an invocation of so, so much (and I don’t believe I’ve read enough praise about that yet. I hope that changes soon, because this work is extraordinary!).

How did you strike the balance between your deep reverence for the world and people of your poetry, while also asking difficult questions of them? I’m thinking of this from an artistic view point, in rendering the tone just so, and maybe from your perspective too as a daughter of this land?

NM: This is a difficult question to answer. In majority of the poems, I tried to lean into a romantic aesthetic. I now see the poems as beginning from a place of having, of abundance, and I think this combination of abundance and a romantic sensibility all work to allow for both reverence and asking difficult questions. My grandmother taught us to always use isimamva nesimaphambili (suffix and prefix) when speaking to people; in Xhosa this is a sign of respect, and I think there is some of this thinking in these poems.

MR: In a review of Peach Country, Niyi Akingbe writes of “the supernatural topography of eMaxesibeni”; could you speak to the sacred and the mysterious, which is not so much woven into your debut as it is of it, in both your poems and your home?

NM; At home we hold Christianity as easily as we hold elements of African spirituality. My aunt and uncle attend The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) which I attended as a young person. I went to a predominantly Indian primary school where we celebrated all the Hindu holidays and had a friend who attended a madrasa after-school on certain days and we would occasionally share stories. I have always had an interest in fairy tales from everywhere. It is against this background that I have great respect for believers. I admire their capacity to hold the natural and supernatural as both holding a fundamental truth. Ubugqwirha nobugqwurha – I can’t think of a precise English way of saying this, I suppose you can go with ubungoma/traditional healing and witchcraft – formed part of everyday life; from those who were on the path to becoming healers, to those who were said to be flying around in bread. We also had stories of Mary in uMzintlava river. After all the stories, it comes down to one’s beliefs, and I choose to never fully take a side. We do not know all the secrets of our world much less that of the universe.

MR: What has the critical reception of Peach Country meant to you? I’m thinking in terms of artistic criticism, as well as thoughts or praise among readers from the Eastern Cape who will know the worlds that your poems evoke?

NM: The positive reception has meant the world to me. When one of my aunts first got my collection, she sent me a voice note analysing my poetry. That was a very heartfelt moment – she said she could see the world I had created in her mind’s eye. I have read Akingbe’s review and thought that my poetry was interpreted in some ways that I had not imagined. I have appreciated hearing from readers from other rural locations in the country, recognising something of themselves in the poems, because I think that rural people and spaces are often ignored in English literature.

MR: I ask every uHlanga poet this question, and I’m particularly curious in your case as Peach Country was your debut. Tell us about publishing with uHlanga. What was this process like, and what drew you to publishing with an indie press?

NM: There was an ease and pleasant slowness in the process with uHlanga. Nick pushed me to think about the golden thread that ties the poems together after he read my manuscript, which is something that continues to live at the back of my mind. Before Nick approached me in 2017, I had never thought of publishing my poetry, so it is safe to say that he drew me to publishing with him when I was somewhat ready to do so.

MR: And two P.S. questions (forgive me!): 1. What surprised you most about the process of putting together a collection? Moving from individual poems to a whole book? And 2. What are you working on now?

NM: I was surprised by how little editing I had to do to the poems because I am someone who fixates, hence my slow writing and limited publication history. I am working on my PhD (cannot wait to submit it!) and writing bad poetry. I had promised my grandfather that we would write something about the history of Lubaleko and his family history, but cancer happened and he passed on a few months ago, so that is something I have been trying to do from what I recall from our many conversations.