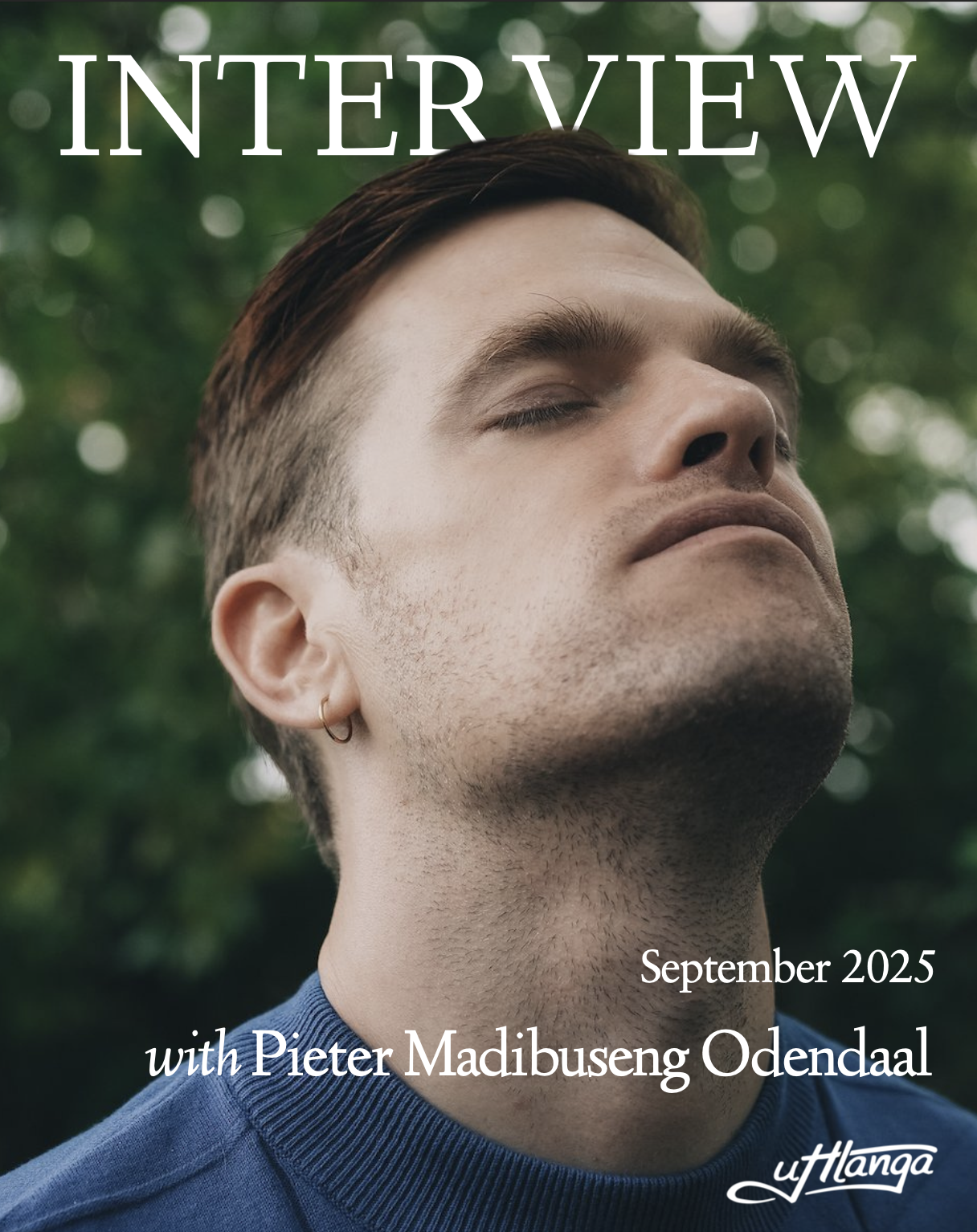

In the latest of a series of interviews with uHlanga poets, Megan Ross chats to Pieter Madibuseng Odendaal about his first collection in English, the questions raised by (self-)translation, and the influence of music on his award-winning poetry.

Congratulations on the publication of a corpse is also a garden! The collection – your first in English, and which you translated yourself – is described as “self-deconstructed”.

I’m interested in translation – in the act of translation, but also, and in your case, the act of translating one’s own work. What was this process like, how did it feel?

The process of self-translation felt like a homecoming via a detour. Finding myself in another language helped me to rediscover the feelings and memories that inspired my poems in the first place, and the process became an interlinguistic meditation on what and why I write. Re-encountering my poems in English also exposed the weak spots in some and revealed the strengths in others, vindicating my poetry while enforcing humility.

Afrikaans is your first language. An onomatopeic language, at once alive and beautiful and strange, it is loaded with a fraught history. What was it like writing poetry that deals with your ancestors, and then translating that into a colonising language, a language like English?

I’ve mostly written in Afrikaans over the years, which has enabled me to confront the fraught history of the language head-on. By bending the language back on itself, I could hold up a mirror for Afrikaans-speaking people, one which hopefully allowed readers to question their own upbringing and the preconceptions and prejudices embedded in their language and culture. Excavating my family history, for instance, is something that could have only happened as brutally in Afrikaans.

But I’ve always felt that my work resonated beyond an Afrikaans audience. Despite the contextual relevance of Afrikaans to my poetry, I’ve long harboured the desire to make my work accessible to more South Africans. These English translations make that larger conversation possible beyond the limitations of Afrikaans.

I’m always interested in this question when it comes to poetry, and new books, and publishing opportunities: why now? You’re an Ingrid Jonker prize-winning poet, critically acclaimed. What took you on this path (I detest the word “journey”) of writing a new collection?

I finally had enough poems to pick and choose from in my first two collections that I could select what I consider to be my best work for an English readership. Now that I’m moving beyond some of the preoccupations of youth, it felt like the right time to also share this work in English.

I would be remiss if I didn’t bring up the title. The title! a corpse is also a garden. I’ve sat with it while creating social media content for uHlanga, while going about my day. Please, tell me about it. Its genesis, the melding together of such opposing concepts (in a way): the corpse, dead; the garden, generative, alive.

I was looking for a title that could capture the ambivalence that characterises my life and work – always the one and the other, opposites bleeding into each other. The title is an acknowledgement of the devastation of (and preoccupation with) death in my poetry, but also holds out hope for the generative consequences of mortality. Life does not stop with death, but simply continues in other forms. The energy stored in my cells and organs will not cease when I die, but will transform into flowers and fungi, sustaining those that are still living.

As an artist, you move between Afrikaans and English. How does writing in English shift your voice, your rhythms, or even your relationship to your audience?

Musicality is central to my poems – being a musician and having performed for most of my life, the way in which poems sound in my mouth and on stage has always been a principal consideration when deciding which turn of phrase, which word, to use. Transferring this musicality to English was one of the greatest joys of the translation process – finding another rhythm and sonority in English that could provide the scaffolding for what I wanted to say.

I’ve always imagined an interlingual, intercultural audience, probably thanks to my days as director of InZync Poetry, promoting spoken word in the Western Cape. So I’m not sure if my relationship to my intended audience has fundamentally changed now that the poems are in English. But I’ve created a different kind of music to accompany them.

Tell us about the publication process: how have you found publishing with uHlanga?

The publication process was a breeze, probably because I had first sent my poems to Marike Beyers, a Makhanda poet and librarian, to edit and proofread, and to help with the order of the collection. Because the preparation was so extensive, once the manuscript arrived in Nick’s hands, there wasn’t much editing left. We took out a few poems and tweaked a line here or there, but the road from manuscript to book was surprisingly painless. Working with a smaller publisher also brought more of a personal touch to the whole process, a real sense that I was being looked after. This ethics of care seems to characterise uHlanga, and I count myself lucky to have found such a loving home for my poetry in English.