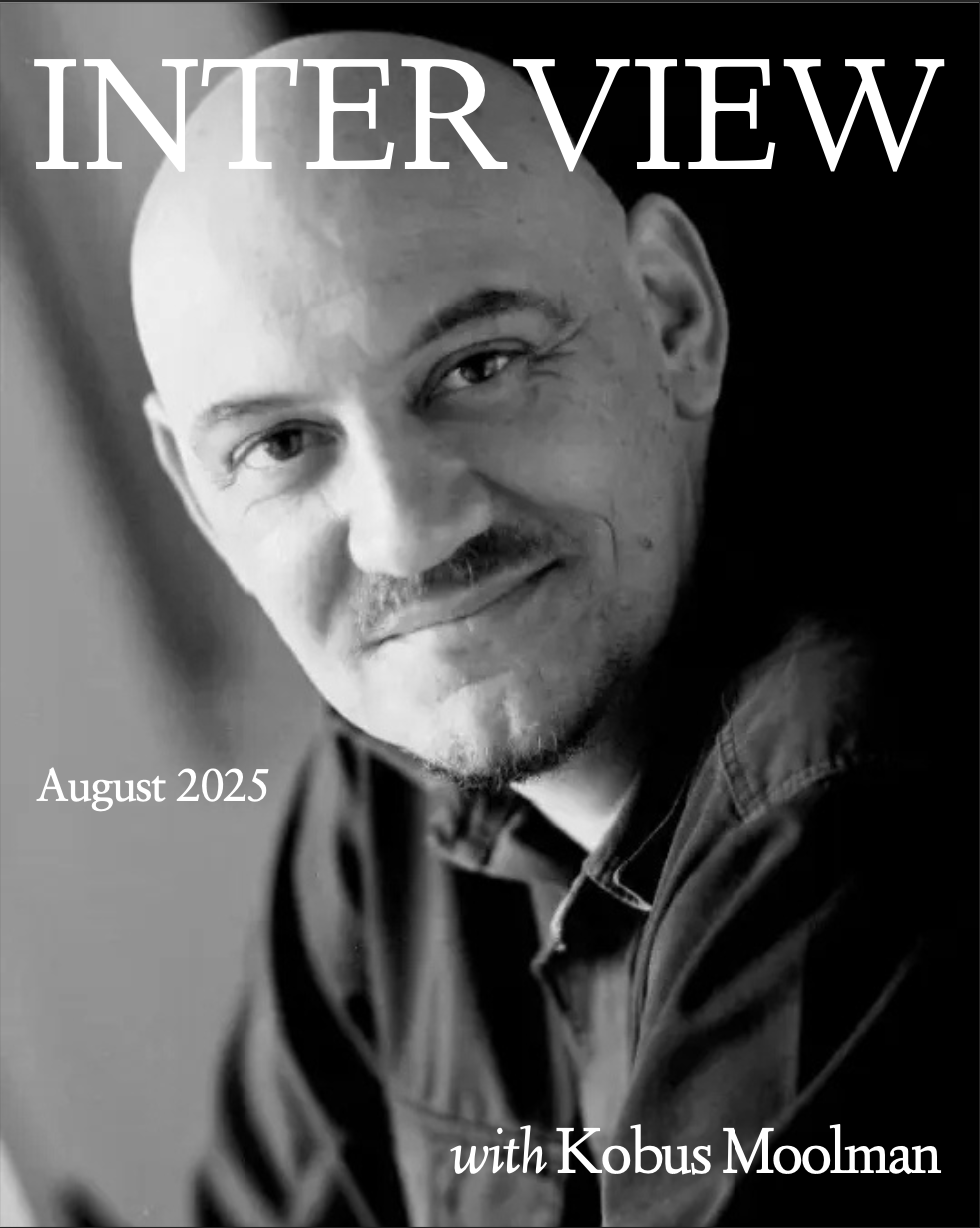

Megan Ross chats to Professor Kobus Moolman about his latest collection, and the very deepest concerns of his long and distinguished career in writing and teaching poetry.

I recently reread Fall Risk, your latest poetry collection, published by uHlanga, and I was struck by these lines:

Skin is a machine

for feeling things

the way needles do.

This is at once an incredibly human image, and yet it also conjures up aspects of the clinical. Could you speak to this?

I think the clinical aspect that you so accurately identify has its origins in specific medical experiences [I have had], which reflect directly upon the collection as a whole. It is where the whole collection comes from in a way and speaks back to. This is both on a personal level historical, in the sense of being disabled since birth and having so many medical interventions over the years, and also recent, now, as someone who has to have monthly immunotherapy. So that’s the one side to the image.

But as a writer the image must move beyond the purely personal. And thus while some poems in the book use the first-person singular – which of course, does not ever have to equate with the author – here there is in fact no speaker. On a certain level you could even say (and I like this idea) that the skin actually is the person or thing speaking, which then allows all skins – your skin, everyone’s skin – to speak.

There is an undercurrent of anguish in the collection, and yet the most overpowering feeling I am left with, upon each reading, is love. Always love. And I’ve felt that in many of your works. Could you tell us a little bit about love? Is it transformative? Damning?

Oh dear. I really don’t know what to say about love. Such a fraught, dangerous, complicated terrain. But yet again, you are very accurate. I might for myself substitute the word ‘compassion’. I am more comfortable using this word.

In all my work – whether poetry or plays or short stories – I have always believed in having compassion for my characters, compassion for the world, compassion for others. I am moved deeply by suffering: human, animal, environmental. And so even when I am writing a horrible, ugly, violent piece – like the poem “the earth is flat” or my short story “Kiss and the Brigadier” (both of which are also very funny) – even then I have to have compassion for the terrible characters and events, and even compassion for the language, which might be twisted and cruel, but nevertheless has to be honest and real. As a writer I have to have compassion for reality.

In one poem in Fall Risk, you write about Anaïs Nin, the Sabbath, and God, and the number seven, and what it could all mean. I left this poem wondering about God and [their] love, or lover. I guess I just want to know, where did this poem ‘come from’? Was it a feeling, a question, a wondering?

And maybe, because I was brought up religious (Roman Catholic), I am interested, too, in the God of and in your poems.

This is big – I honestly don’t know how to answer you. How to answer without actually just referring you back to everything I’ve ever written. How not to close my eyes and cover my eyes with my hands and just say nothing. Because nothing I say can summarise or describe my response to God – the idea of God, Gods, that, there, it, nothing, no-thing, light, dark, depth, infinite, mystery. Just the whole lot wrapped up into a tangle of stuff. And hard to separate one’s past, growing up in a strict Calvinist background. NG church. And hard to separate those terrible ideas of guilt and punishment that cling to one still – despite all the scrubbing. But, in fact, the plain simple truth for me is that I do believe in something before and something after and something outside and something within all everything and suffused through all and beyond at the same time. And this whatever we call it – leave all the pronouns far behind – this is the origin of every single small and big and beautiful and ugly thing I have ever written. That ultimately I am not the source. The source is the Dark Light.

In a recent interview with Quinton Mtyala on IOL, you said:

“I've begun to understand the body and the relationship between the body and language, and different bodies using language differently, and how language can be used to show the body in its differentness.”

I’d love to hear more about this, about the capacity of language to, as you say ‘activate’ something in someone, perhaps, in a way, give them a chance to convey the uniqueness of their humanity, or their experience of living in a body.

Again, this is the pursuit of Fall Risk, and most of my work over the last decade perhaps – an attempt to explore, to understand, and even to represent the multiple ways in which the body speaks. And I know that this term has become a little bit of a cliché. Kind of tossed around too easily. Without real in-depth and felt engagement. But for me it is felt. It is actually lived. It is a daily, lived-in experience. As it is for everyone in fact. But more often than not for many people the body is a triumph. A site of pleasure. Achievement. Strength. But what about those moments when it is not? When it is the opposite? What about a life lived in that other encounter? How to talk from or about this encounter? And the only way I have learned, and am still learning, struggling through, is to actually talk from this encounter.

One of the most poignant lines, in my humble opinion, in Fall Risk is “I want to evaporate.” Is this a meditation on mortality, or the imperfectness of a human body, or is it more of a longing to just become a part of the natural fabric of the world?

It’s all of the above. And it’s also Keats’ idea, “to cease upon the midnight with no pain”. To be released.

[Long pause.] I think that’s enough of an answer.

You have published over ten collections of poetry. What is it about this medium that returns you to it, over and over?

I’m a sucker for punishment, I suppose. [Laughter.] But also because actually I haven’t said it. I’m not done yet. It’s still unfinished. I am still unfinished. I am still in search. Still looking for it. What’s that line from U2? “I still haven’t found what I’m looking for.” Plus, I am hungry. I am perpetually hungry.

I read that you teach your students to write a poem. And I love that. I don’t think I’ve ever been taught to write a poem… What has teaching poetry added to – or even taken away from – your experience of writing it yourself?

Phew! I love all your questions, Megan. But they are exhausting. Exhausting because they take me to the real deep centre, the challenges I struggle through on a daily basis.

I love teaching. I really do. I love helping young people – students, whomever – understand something about themselves and their relationships to the world. Literature and art is one of the fundamental ways of doing this. And teaching the practice of making art for yourself – of making your own art – has helped me understand more keenly how I make my own art.

But yes, if I have to be honest, honest with myself, then I know that it is taking a toll. It never used to. I was stronger. I was able to sustain, endure, live through the arduousness of the process. Arduous because each time I teach how to write I am going through and experiencing that “blank incapability of invention” that Mary Shelly described in her preface to Frankenstein. It is becoming increasingly difficult to keep doing so.

Much of your work is deeply rooted in the South African landscape, yet it often has an otherworldly or dreamlike quality. How do you balance the concrete and the surreal?

It must be both. That is what I strive for. One of the ways I have discovered how to do this is to be as plain and direct as possible to name the thing or things as they are. To force attention so that the reader sees or hears, smells, differently. Or smells the old tired thing in a new way. Shklovsky called it ‘defamiliarization’. That’s exactly it. Rendering the real with sharp and stripped, concentrated focus – through the language of poetry – weirdly, magically, releases or activates this ‘dreamlike quality’ that you speak of.

And finally, I’d love to chat a little bit about publishing with uHlanga. What was this process like, and what drew you to publishing with an indie press?

I’m not intending to flatter you or Nick in any way. But I have profoundly respected the collections that uHlanga has published. I’ve respected Nick’s enduring and passionate commitment to South African writing, specifically poetry. And I’ve wanted to be part of this. Indie presses are where the real fun is to be had, certainly with regards to poetry. Look at presses like Deep South, Dye Hard, Karavan and Modjaji – they are publishing real stuff! And Nick has just been an absolute pleasure to work with. He hasn’t paid me to say this! [Laughter]