In the latest of our series of interviews with uHlanga poets and translators, Megan Ross interviews Richard Whitaker and Douglas Reid Skinner, the translators of Catullus: Selected Lyric Poems, a selection from the bawdy, sometimes scandalous oeuvre of one of the late Roman world’s great poets. Their joint translation project was published in 2020 by Crane River, and is distributed by uHlanga.

What first drew you to Catullus?

RICHARD: I first read Catullus in English, in the 1960s racy, free-verse, Penguin translation by Peter Whigham, and I was completely hooked. Catullus’s poetry was so immediate, so contemporary, by turns delicate, ferocious, tender, laugh-out-loud funny, wonderfully obscene. After I learned Latin, I enjoyed his poetry even more in the original.

DOUGLAS: A late 20th-century American book of dual translation; on close examination, it was clear the translator had wandered too far from the original texts. Richard’s 2017 translation of Homer’s Odyssey got me thinking a more accurate and contemporary Catullus might be worthwhile.

How do you navigate the emotional and tonal range in translation?

RICHARD: It’s not easy. Catullus has a very wide emotional and tonal range, and he uses a great variety of Latin poetic meters and verse forms. You try to represent the range by selecting just the right level of English vocabulary, the right individual words, the right rhythm and form for each poem you translate.

DOUGLAS: One’s best chance of working out the subtleties of usage and cultural connotation appears to reside in finding a sense of the person in the poems and their characteristic emotional pitch.

Do you ever let your own poetic voice slip into the work, or is the goal to stay invisible?

RICHARD: One can’t “stay invisible”. Who you are, your personality, what you have read, what you have written – all of that is going to inform how you translate. You try to open yourself to the poet you are translating, to represent as much as you can of the original text, but inevitably there will something of yourself in the translation.

DOUGLAS: The first is, in varying degrees, inevitable. And invisibility is, in a way, impossible as one’s intention is to transport the other into a particular now and here of which one is a part.

What’s the biggest challenge in bringing ancient Latin into modern English without flattening its texture?

RICHARD: My answer would be like the one I gave to your question about emotional and tonal range. As a translator, you have to try and find some sort of contemporary equivalent in English to the Latin meters and words that Catullus used. If you are successful, the translation should convey now, today, the spikiness, smoothness, delicacy, or harshness that Catullus expressed then.

DOUGLAS: I like to think of a translation as a kind of diplomat who shuttles between two cultural worlds. There are always compromises to be made on both sides of the equation.

Is there one poem that gave you the most joy — or the most trouble — to translate?

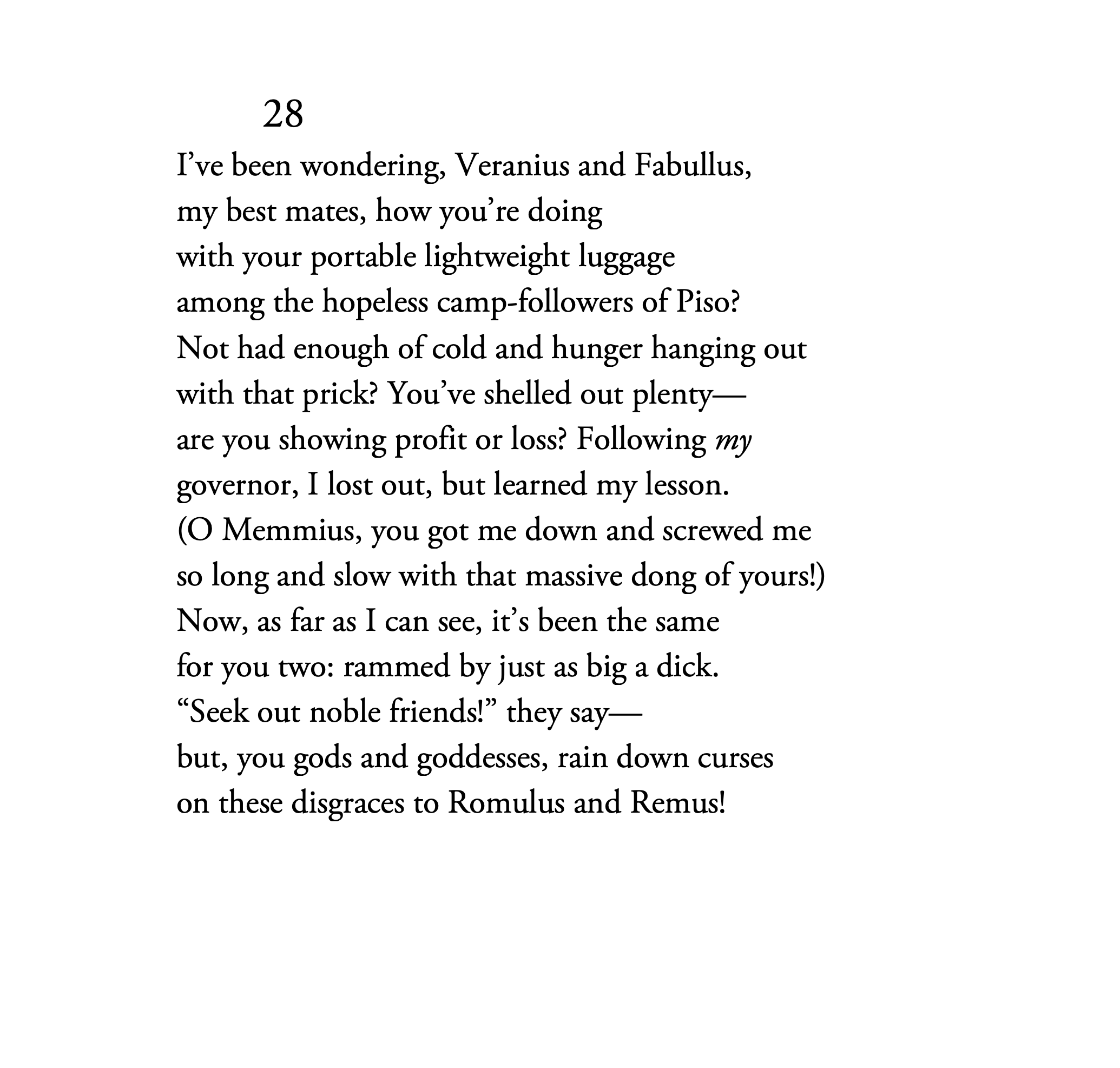

RICHARD: I think that overcoming difficulties in translation also, often, brings the most pleasure. I loved the tricky challenge of trying to catch the offhand, conversational tone of a piece like poem 10: “I was hanging around idly in the Forum . . .”, where Catullus ends up embarrassed at being caught out in a white lie; or the similar tone of the casually obscene poem 28 addressed to two mates of Catullus who have been screwed over by their boss, just as the poet was by his.

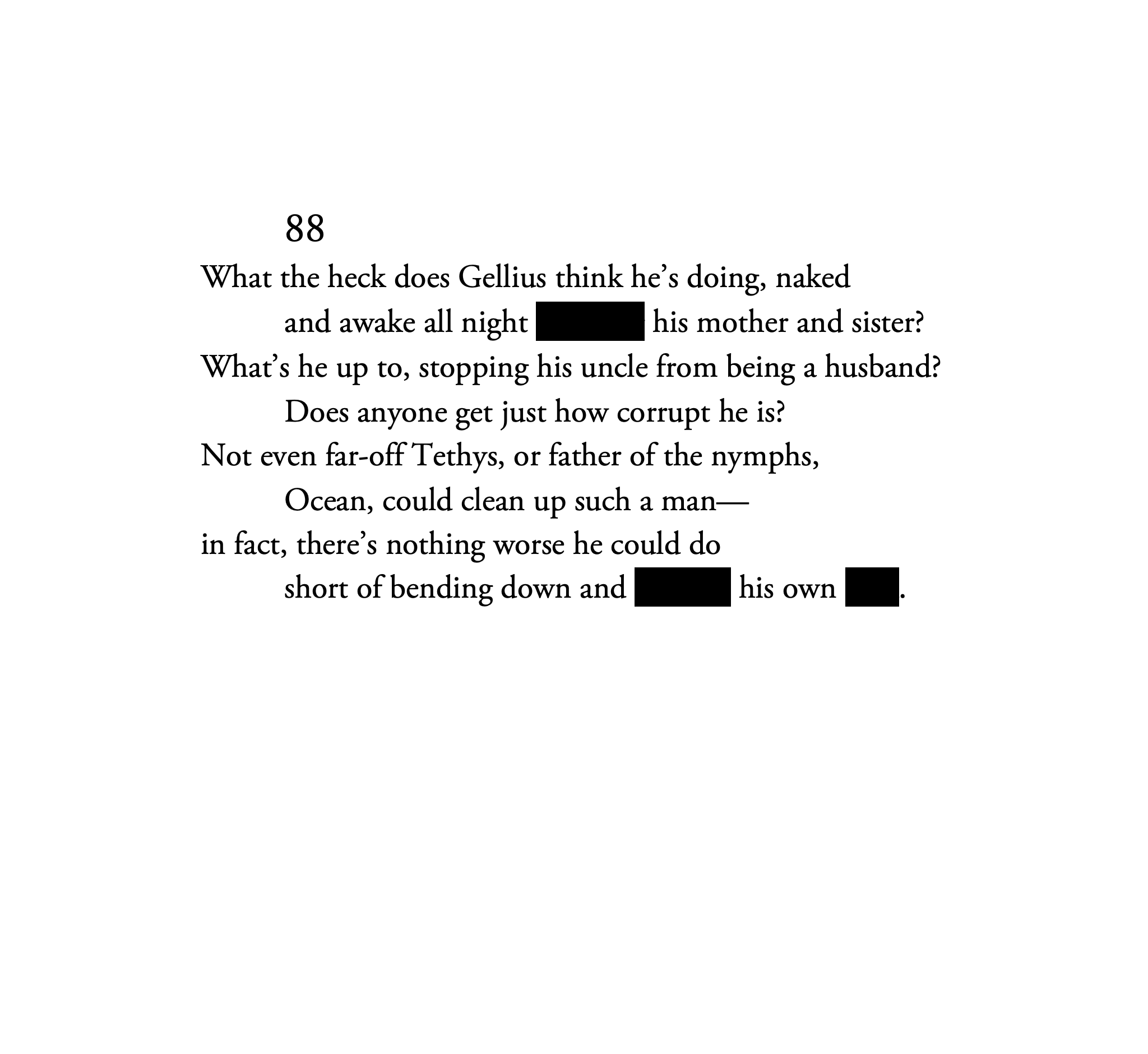

DOUGLAS: Getting the more ribald ones right – for instance, poem 80: “What’s to say, Gellius, about why your rosy lips . . .”, or 88: “What the heck does Gellius think he’s doing, naked . . .” – was the most fun. It allowed for a creative use of demotic.

What do you hope a modern reader, especially in South Africa, discovers in Catullus’s poetry today?

RICHARD: I hope that this translation can bring modern readers the same shock of delight and recognition that I felt when I first read Catullus, the sense that here was someone who seemed to be absolutely my contemporary. And I’d hope, certainly, to win new readers for Catullus in South Africa, where the poet is generally little known.

DOUGLAS: One of the extraordinary things about Catullus is his psychological contemporaneity despite a great gulf of historical time between him and us.