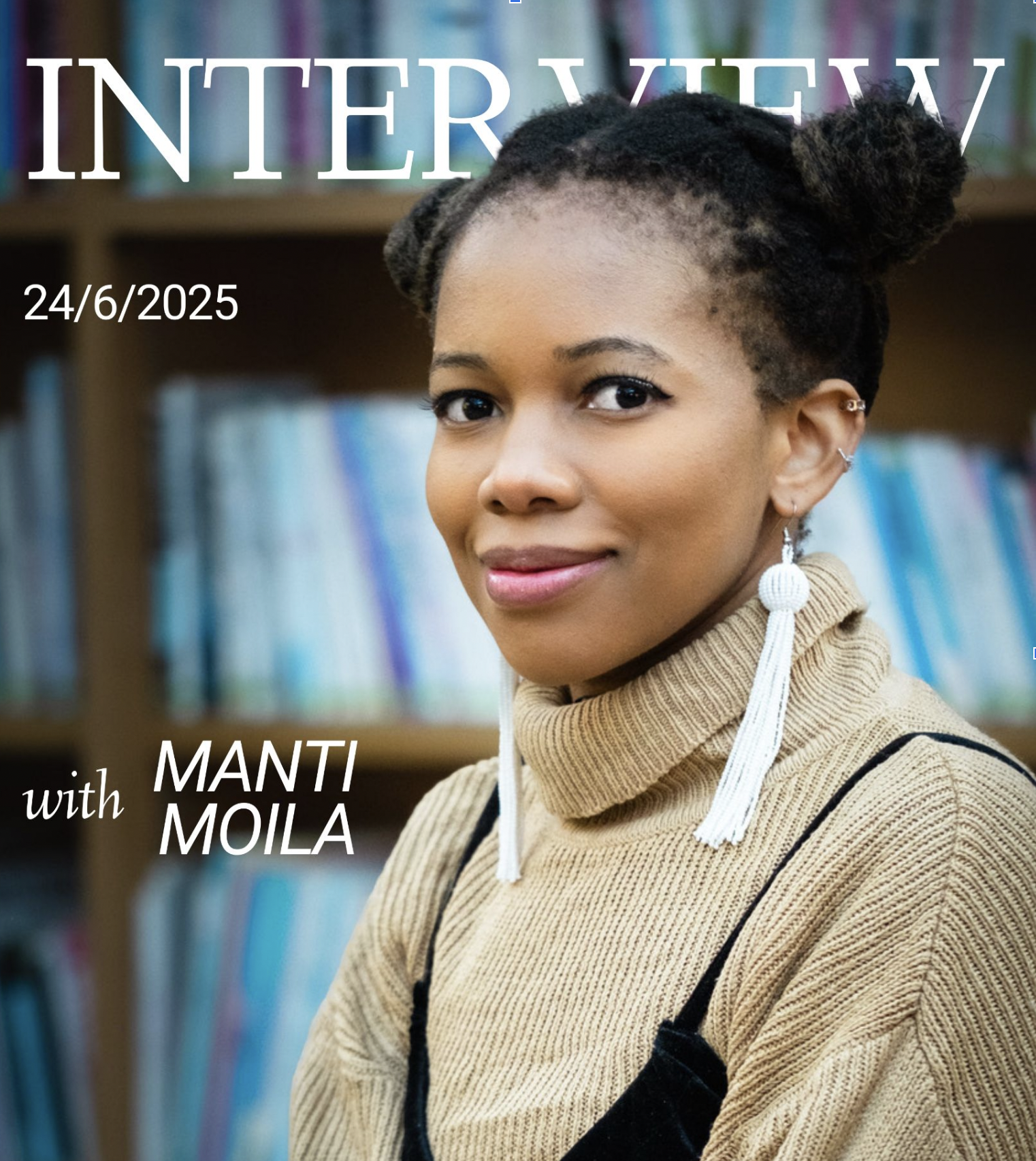

In this wide-ranging interview, Megan Ross chats to debut poet Manthipe (Manti) Moila about her poetry collection Rootbound, the joys and limitations of language, and the poets who influence and inspire her own work.

Congratulations on Rootbound! Can you tell us about the journey of writing your debut collection? What was the seed that grew into this book?

Thank you so much. The journey of writing Rootbound was like a journey to myself. I had a couple of attempts at writing a collection that were lacking because I didn’t have the tools or courage to explore the matter at the core of the collection, which is that of my first heartbreak. My relationship with my father was a complex one, and I always thought he would return, after unceremoniously dipping from my life, but he never did. His death made all the conversations I wanted to have with him an impossibility. So I used literature as a medium to say what I needed to say.

The title, Rootbound, is evocative and layered. What does it signify for you, and how does it reflect the central themes of the collection?

Yes! I had three titles in mind and though Rootbound was the least flashy, it definitely was the one that did the most heavy lifting. On a surface level, the title is a nod to the botanical motif that threads through the collection. However, the title is also a metaphor for the state the speaker of the collection starts out in: stifled, trapped, in need of a new environment. One’s ‘roots’ are also seen as the true, eternal home. To be alienated from your roots is necessarily to have an identity crisis of existential proportions. In a more globalized landscape where cultures shift constantly, I wondered if there was room to complicate this narrative. What does it mean now, in the digital age, and in the age of mass migration, to feel at home, or to have roots? I’d love to give the reader room to make their own connections, and make the collection theirs.

Many of your poems wrestle with identity, belonging, and memory. How do your personal experiences and background as a South African shape your poetic voice, especially with your being based in South Korea? (I lived in Bangkok for a while, so I am so excited to read a collection by another African poet whose feet are currently in Asia!)

I know I’m probably not supposed to say this, as in literary and academic spaces it’s a big no-no for the speaker and author to be seen as one, but I want to answer earnestly: this is a deeply personal book and my experiences have shaped it as a work of art. I drew directly from my experiences when writing, as I wanted to feel anchored in my writing. For example, there is Korean incorporated into the collection. I did not do that just because I thought it would look cool – it’s more that the Korean language is also something that I am grappling with. It’s difficult, I’m not as good at it as I ought to be by now, but I love the language. I also operate in the language on a day-to-day basis, so it made an impression on me that I wanted to be reflected in the book. I now find it fascinating that I can get through a (simple) Korean novel but not even a picture book in my mother tongue. Identities are so much more slippery and complex, I think, than we would like to admit. The spaces that the body occupies, be they physical or psychological, leave their mark.

Your work blurs the boundaries between the natural and emotional worlds. How do you use nature as metaphor in your poetry?

I find that phrasing interesting, as it kind of touches on one of the things I was contemplating while writing the collection. I wanted the different stages that a houseplant goes through to reflect or run parallel to the speaker’s own journey. However, houseplants are just that – a use of nature, a manipulation of it. I sometimes have trouble contending with the natural world in all its glorious terror. Houseplants are a manicured, clamped down version of nature that affords people some of the benefits of nature – beauty, calm etc. – without having to deal with the threatening aspects. The word ‘bound’ makes up half of the title for a reason: I love my houseplants, and my plant poems, but there’s something to be said about how we are incapable of reigning over nature, even in language; or especially in language.

Were there any particular poets, books, or artistic influences that guided or inspired you during the creation of this collection?

Funny that you ask – you’re actually one of them! I love Milk Fever and I would underline lines I loved, read and reread poems, pluck out certain words from your verses and try to turn those into poems of my own. So this interview truly is a full circle moment. Others who I drew from were Maneo Mohale, Mark Strand, Ocean Vuong, and I.S Jones. In fact, in the collection there are poems that draw from specific lines in poems I admire. I found, and became obsessed with Wallace Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”. There’s my attempt at a contrapuntal inspired by Safia Elhillo, and a dialogue poem inspired by Franny Choi and Sumita Chakraborty. For me, poetry begets poetry, and though I currently draw heavily from my experiences, I also draw from individuals or individual poems that I admire.

Poetry can be both deeply personal and universally resonant. How do you navigate the line between vulnerability and craft in your work?

Well, I hope! There’s room for both in poetry. There’s room for anything in poetry really – it’s a house of endless rooms. That being said, I think that in order to keep from drowning one’s work in sentimentality, craft needs to be a practice. I try to be as vulnerable as possible in the initial stages of penning a poem. That’s the only way I can get it out. Then, as I become more distant from the poem – after having put it away, or getting feedback on it – I use my craft skills to give the poem shape, form and coherence.

Craft is one of those things that I’m consistently working on. For example, when I was writing the collection, I was reading Diane Lockward’s The Crafty Poet: A Portable Workshop, as well as The Poet’s Companion by Dorianne Laux and Kim Addonizio (I’m still working through them actually). I also would do online writing workshops with a friend in which we opened each session with a poem and some poetry analysis.

Photograph by Rae Ann Bochanyin

How has working with uHlanga shaped your experience as a debut author? What was the editing and publishing process like for you?

It’s been a dream come true. Editing was really fun, initially, then I kind of freaked out towards the end as we neared the completion of the collection. I find it really hard to edit, especially poetry because when is a poem really done? The answer could be after the 6th draft or it could be never. I’m glad I had Nick to give his perspective on the work, but also to help me manage my anxieties and insecurities. There were bouts of imposter syndrome that hit so hard I would wonder if my poetry would ruin poetry itself. I couldn’t have done it without uHlanga, and my friends and beta readers who were there for me throughout the process. Publishing has been challenging since I’m so far away from home and feel quite at a distance from the collection though it is out in the world. I wasn’t emotionally prepared for that. So after giving it more thought, editing and publishing have been quite difficult actually, but I think that’s the nature of the work.

What do you hope readers will feel or take away after reading Rootbound?

I don’t really want to impose too much. I know what the collection means for me, and what I currently take away from it. However, each reader brings themselves into whatever they are reading, and they kind of co-create the world of the book, poem, whatever it may be. Sure, I have themes, organising principles, a singular speaker (mostly) but I think it’s up to the reader to work with what I’m giving them and come away from the work with whatever they want or need. It’s a very scary prospect for my work to no longer belong to me in that way but I feel like it’s also appropriate.

And lastly, are you working on anything new (that you could potentially tell us about)?

I can dish a little bit. I’m working on a story-in-verse set in a pre-apocalyptic/apocalyptic world. It’s a huge departure from Rootbound, very challenging and currently probably a little beyond me. But I’m teaching myself how to write the book as I go. It’s something I’ve been wanting to do for a long time so I’m excited to see how the project shapes up.